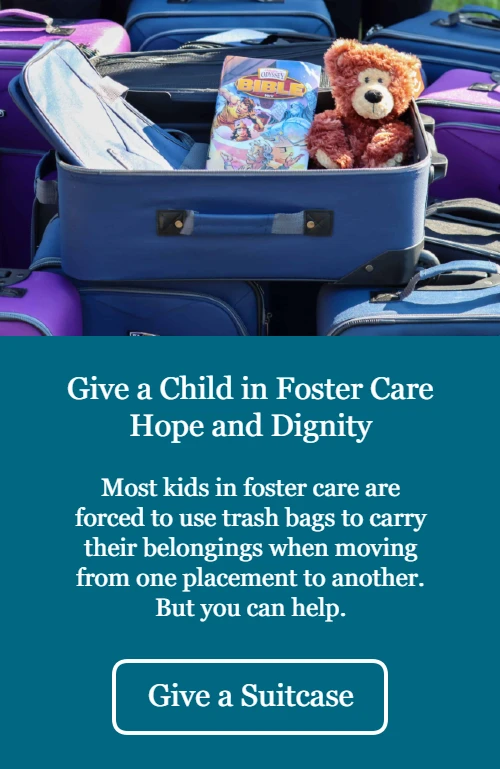

When most children get hurt or become afraid, they go to a parent. After all, parents are the ones who protect children and comfort them. For these children, it’s a simple equation: Mom and Dad are safe, and I can trust them to help me.

But things aren’t always that simple for children with histories of early harm such as trauma, abuse or neglect. Developmental psychologist Karyn Purvis, co-author of The Connected Child, refers to these kids as “children from hard places.” Their life experiences often make them prone to prolonged states of fear and a limited ability to trust.

This is particularly true of children adopted through foster care. Instead of going to their parents for help or comfort, these children often run from them, push them away or shut them out. This can begin a downward spiral of frustration, leaving the child in desperate need of connection and the parent desperately wanting to connect.

As a father to four adopted children, I’ve seen this play out in my own family. Our children have experienced various challenges over the years, and my wife and I have at times struggled with how to respond.

I remember when we were playing basketball and one of my sons (then 6 years old) fell and cut his knee.

As I approached to help him, he became angry and yelled at me before running off down the street. I was stunned by his reaction, and as I followed after him, I thought: Why is he running away? Doesn’t he know I’m here to help?

I’ve learned that many children from hard places respond in similar ways to stress and fear. This happens not only when they are injured, but also when they are sad, embarrassed, frustrated, lonely or angry — even when they are tired or hungry. In all of these situations, their reactions can look a lot like willful disobedience. In turn, parents often respond by coming down hard and using discipline that physically isolates their child and leads to greater emotional distance.

Instead, parents should strive to close that distance, even as their child pushes them away. They need to resolve conflict and respond to misbehavior in ways that both correct and connect. My son who ran off needed me to understand what he was feeling, not just focus on his behavior. When I finally caught up with him, the first thing I did was listen; there would be plenty of time later to talk about what went wrong.

At that moment, he needed me to convey a simple message: You are never alone.